Conclave at the End of the World

papal memes, post-ironic Catholicism, and gazing unflinching at God

Roman Catholicism is everywhere, from headlines to high fashion to edgy meme accounts. Every art-scene it girl you know has been photographed on the streets of Bushwick with a cigarette and rosary in hand, brands like praying have gone viral for their God’s favorite merchandise, and Tiktokers are arguing in comment sections over whether women should veil during mass. Five years ago, only parochial school veterans knew what sede vacante1 meant. Now, cultural critics brand themselves as sedevacantists2 in their Instagram bios with the same droll affect of thinkpiecers describing themselves as “libertarian” in 2017.

When Pope Francis died, the eyes of the world turned once again towards Rome. We collectively held our breath to see who would be chosen next, whether we were devout believes or merely curious outsiders. And I, as a terminally online Zillenial with a theology degree, enjoyed watching the web becoming temporarily fixated on one of my pet interests.

The moment white smoke poured from the chimney of the Sistine Chapel, I was inundated with a flood of text messages and, of course, memes.

“Let’s go CHICAGO 🦅”

“What do we know about the new pope?”

I opened my DMs to readers and colleagues sending me habemus papam memes because conclave is like your Met Gala, right? What do you think of the new guy? Even the most areligious among my peers wanted the hot Vatican gossip, and their offerings of connection and care came, most often, wrapped up in humor.

If you ask me face-to-face, I’ll tell you I’m not Catholic. If you ask me within earshot my friends, they’ll roll their eyes. They know that my psuedofetishistic, mostly antagonistic, and half-ironic relationship to Catholicism has evolved over time into something more complex. Something dangerously close to sincerity.

In the same way my loved ones knew I was bisexual before I did, they understood before I did that the frequent exploration of Catholic iconography in my novels, the vintage rosaries hanging from my vanity mirror, and the laminated cards of Saint Ignatius and Mary Magdalene in my purse were not simply decorative. My friends have taken my late night calls about eternity. They’ve seen the way I soften and settle in old cathedrals, like a mourning dove brooding in her nest. They know what’s real and what’s for show.

To be loved is to be known, even and often when we do not know ourselves. How beautiful, to be loved in this way.

And how sobering, to be known for an identity I’ve spent a lot of time performatively denying. This denial sometimes takes the form of semantic hair-splitting, but it’s most often done through ironic humor.

My disavowal is not unique. The sincerity drought has been covered widely, most recently by Tiffany Ferguson in her video essay “irony, cringe, & fear of being perceived are ruining our lives” (in which my writing is quoted, thank you Tiffany!). I’ve written about irony poisoning before, but suffice to say, an oppressive sense of ecological and political doom, economic decay, and a media landscape of extreme atomization and disinformation make it hard for people to look their own lives straight in the face. And truly weighty things like death, sex, religion, love, and suffering …Well, we can only speak of them with a wink, a wince, a wary glance over our shoulders.

So in the interest in getting sincere, let’s lift the curtain on this cultural turn towards Catholic imagery and piety. Is it all just aesthetics and shitposting, or does the myrrh-scented cultural moment guide us towards something deeper?

Nine years ago, I was studying for my masters in theological studies at Princeton Seminar. I was in the earliest stages of discerning whether I wanted to pursue ordination in the Episcopal Church, and I was trying to figure out how to walk the tightrope between radical authenticity and adult responsibility, to do something meaningful with my life. At this time, I was also was becoming increasingly preoccupied with Roman Catholicism—caught in that charged space between desirous and disdaining.

So many bright spots drew me to Catholicism: the communion of saints, the harrowing of hell, Ignatian contemplation, the transformative power of ancient prayers, mysteries and the miraculous, the fortunate fall, transubstantiation, social teachings centering human dignity and worker solidarity. But when I drew closer to those lights, curious to see what they would illuminate within me, I got burned. By the Church’s brutal history of conquest and colonialism, but the broken spirits of my queer siblings, by clericalism, by Inquisitions and pogroms, by the repression of the feminine and silencing of women, by the leagues of red tape and insularity.

And of course, there was the taboo to contend with.

I was raised evangelical3. It was religion of hyper-vigilance: being Good meant believing the correct things, really hard, all of the time, and expressing those beliefs through cultural markers like not showing cleavage and not watching R-rated movies. Despite the bloody midnight showings of The Passion of the Christ and the sweat of the summer revival tents, it was a faith that lived in the mind and heart, not in the body. The body was an afterthought, a hinderance, a stumbling block. The body did not participate in the cultivation of virtue unless it was carrying out acts of charity, so there were no candles, no rosary beads, no kneeling, no chanting, nothing to distract from pursuit of Perfect Mental Purity. Those practices were dark, psuedo-pagan, probably occult, and worst of all, Catholic. These words blended together in my child’s mind without much meaningful definition.

Over time, my strong attraction to religious ritual swirled together with my sexual desires, my ambition, my anger, my Faustian appetite for knowledge, and my resentment towards unchallenged male religious authority into a malestrom of shame.

Stumbling into the largely liberal but liturgically traditional Episcopal church was a lifesaver, and it’s true that I loved the Episcopal church on her own merit. But I knew in my guilty heart-of-hearts that I also loved the Episcopal Church because she was as close as I could get to Catholicism without betraying parts of myself that felt essential to my survival.

When I spoke of Catholicism it was always with an eyeroll or a lascivious wink. I was terrified by the sharp, straight arrow of my desire pointing right at Rome, so I tried to bend that arrow with humor into something cooler, something chicer, something that resulted in less social consequences among my family and my progressive peers.

How could I possibly explain that my draw to Catholicism was deeper than philosophy, more profound and more ancient? How could I speak of the goosebumps pebbling my skin when the golden altar bells rang, the way I tasted roses whenever I knelt at the carved feet of a statue of Mary?

Decadent Irreverence

For the next nine years, irony protected me. It ensured that if anyone got too curious about my private, quiet study of Catholicism, I could brush them off. I never spoke of religion directly, because everything I had to say was in between the lines of my novels, stories where sex and God and religion and magic blur profoundly. My irony guaranteed that nobody within my church took my faith seriously enough to decide that I was in need of correction, and that nobody outside the church became nervous I was some of kind of sleeper crypto-conservative4. Crucially, it prevented me from dealing with the guilt of opting into a faith tradition that so many of my loved ones had barely escaped with their lives.

I’m was queer woman and an artist and avowed hedonist for God’s sake, I should know better than to think the Catholic church is my friend!

Luckily, I was in good company among the neo-aesthetes and modern decadents who venerated Oscar Wilde and Donna Tartt and Sebastian Flyte and all those other louche, disaffected characters with their tragic spiritual longings. Catholicism was a beckoning box of colorful paints, a rich text we could plunder for aesthetics and evocative imagery that didn’t have to be linked to sincere faith. It was kind of sexy anyway, to slam gin martinis on Friday, spend Saturday writing tortured gay poetry, and then show up to mass on Sunday seeking something transcendental. It felt like we were carrying on a time-honored tradition. As First Things senior editor Julia Yost wrote for the New York Times: “The Decadents knew that Catholicism pairs well with transgression.”

But everything repressed will rise again, and not every dark urge of the human heart can be sublimated into art.

In this way, the trad cath provocateurs were inevitable.

Unfortunately, We’ve Got To Talk About JD Vance

The ironic-until-it’s-not turn towards Catholicism among influential artists, designers, and political figures does indeed skew quite conservative. Converts Candace Owens and US Vice President JD Vance are straightforward and loud about their traditional doctrinal beliefs, but there are many who are harder to pin down, figures who move between based jokes and hard-line theology with a fluidity unique to the internet age. Let’s call them the Dashas5 of the world.

Mikkel Rosengaard summed the archetype up in his article “Age of the Femtroll, or the Based It Girl” in Flash Art.

“With her online excesses and trad cath pageantry, the femtroll belongs to the decadent tradition. Everything she does is vulgar, distasteful, morally debauched, like the dandies of the fin de siècle. Joris-Karl Huysmans, Oscar Wilde, and Joséphin Péladan, who, like the Based It Girls of downtown New York, turned their backs on what they saw as a degenerate society and fled into artifice and religious fantasy.

Like the decadent dandy before her, the femtroll is reacting to the wave of middle-class hypocrisy that always crests in the wake of a great moral panic.”

The Dashas of the world dabble with decadence even while disavowing it, opine about the Fall of the West with a straight face while wearing vintage lace slips to their arthouse interviews.

The connections between the decadents and the Dashas and the die-hard neo-Conservatives are more of a spider’s web than a continuum, and I urge us not to flatten them all into a single subculture. However, they’re certainly shaped by the same milieu.

Since the naughties, there’s been a demographic shift among young people away from mass market evangelicalism and towards “high church”6, a pipeline supported not only by socio-cultural and political factors, but by a stirring in the collective psyche for something more meaningful than 2000s pop spirituality. We were burnt out on a spiritual culture composed entirely of good vibes and a nebulously benign universe and a horoscope thrown in here and there. That framework demanded nothing of you but promised little in return. You were left with pockets full of crystals but no sense of place, of purpose, of piety.

Enter the Vatican.

Is it any wonder than in a world where truth has been categorically eroded, we want to be told what’s right, even if it’s just so we can articulate our opposition? Is it so strange that in a culture where quintessentially human pursuits like romance, art, and ethics have been outsourced to algorithms, we’re all hungry for a more filling meal?

The it girls and podcasters have spoken: it doesn’t matter if the meat’s a little bloody, if the dark sauce turns our stomach, so long as religion is serving something of substance.

Whose Afraid of Irreverence?

Op-eds love to hand-wring about whether the faith of these trendsetting converts is “authentic”. I think they’s asking the wrong question. If Catholicism is something done in the body, a rhythmic practice that shapes the soul like ocean waves shaping rocks, there’s actually not that much difference between doing something for the aesthetic or out of devotion. Calling someone a cringe poster or a promulgator of poisonous ideologies might make for good content, and you might even be right, but it has nothing to do with whether or not they’re a “real Catholic”.

Follow the arc of irony long enough and you’ll come right back around to sincerity. At a certain point, the only scandal left to us is honesty.

Which brings us to shitposting about the pope. What does the very human urge to memefiy the pontif say about our collective relationship to the divine?

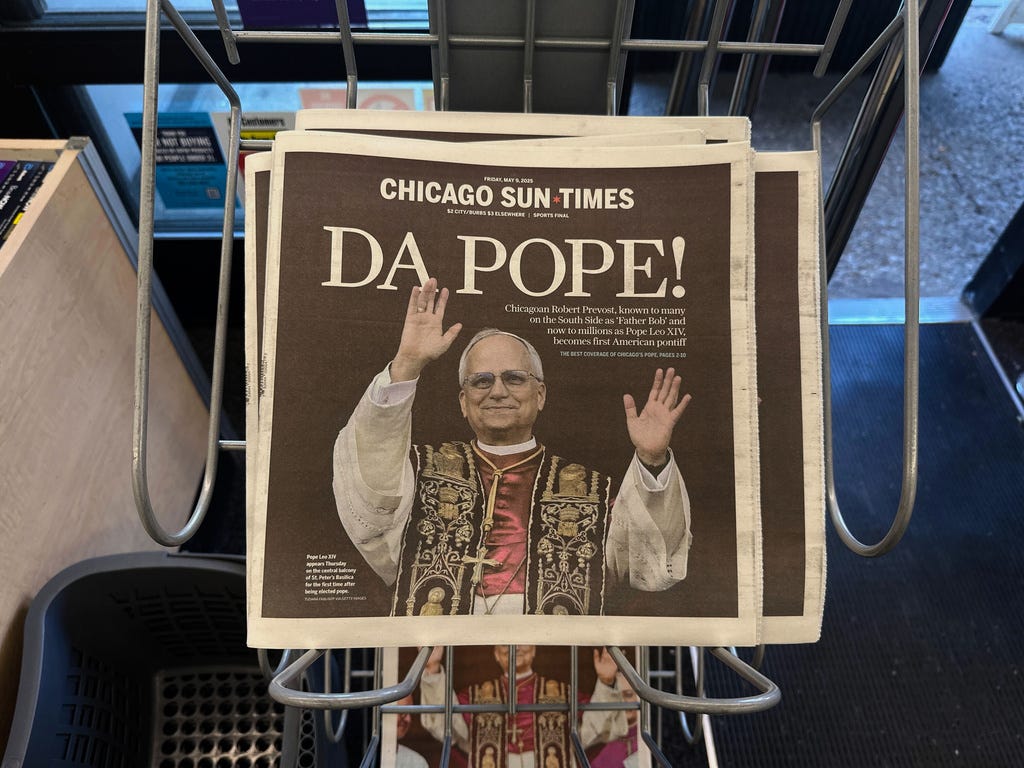

I loved this quote by Ashely Lenz in an on all the Chicago-style jokes bubbling up around Pope Leo XIV: “There’s just a lot of joy in the city right now. There’s a certain delight of seeing something sacred break into the ordinary.”

Strip back layers of culture, and isn’t that what the mystical heart of Christianity is about? Holiness finding incarnation in flesh and sweat and tears, the sacred rubbing up against the profane until something catches fire, taboos dissolving in chalices of sanctified wine and banquet tables open to all? The sensuality of an unmarried woman washing the feet of God with her tears, the suffering of a mother screaming at the site of of her son’s slaughter, the transgression of all castes of society mingling in baptismal fonts underground while Caesar slumbers above? As the apostle Paul knew intimately: What God has made clean, you must not call unclean.7

Authentic Christianity is definitionally countercultural8, carnal, and communal. At the risk of sounding like a youth pastor, the religion has always been deeply transgressive, that’s why there’s also been such an imperative to absorb it into hegemony. The real question we should be asking here is: what boundaries and norms are we willing to transgress? And are we doing it out of a desire to secure our own resources and safety, or to better the world?

I don’t think Catholicism — or religion at that rate — is the right path for everyone. But I do I think that if you’re drawn towards a faith tradition, you owe it to yourself to see what that longing has to say. And if you decide to make your home there, you owe it to the world to work within your tradition for justice, compassion, and peace. That is the great work of being alive, even when the idols of algorithms and internet clout and respectability fall away.

A Heart Pierced By Swords

I stop dead in front of a statue of Mary on my walk home from happy hour, looking up at her with tears in my eyes. “They think you’re holy and you are,” I say, like she can hear me, because she can. “But you’re also just a teenage girl. You must have felt so alone and so scared.” I feel closer to her in that moment than to any other human being.

I tell the priest that I just want to be good, the kind of good that promises clarity of artistic purpose and that all my suffering will be alchemized into some higher purpose. He tells me that I don’t deserve to suffer just to so strangers can actualize through my art. I tell him I need to confess. He tells me I might need a friend too, invites me to call the number on his card if I ever feel too alone or too scared.

When a beautiful woman asks me about faith in a dark lounge, I gaze at her mouth and tell her about the Jesuit teaching that even our most banal desires are gifts, compasses of needy want pointing us towards the heart of God within us. Her eyes sparkle in the dim glow of the tealights, on fire with a desire that might be for me or for divinity or for a good story, or more likely for all three. In that moment, I cannot even remember fear. I can’t fathom feeling alone.

The truth is: Catholicism is one of the only things in life I have chosen for myself. It’s is a sprawling, baffling, bloodstained mess but it’s mine. I love it too much to pretend I don’t care. I certainly love it too much to cede it to reactionaries.

In a recent Back from the Borderline episode, Mollie Adler said: “Most Christians…haven’t touched the contemplative root of what they’re worshipping. What they have inherited is mostly dogma, fear, politics, and a handful of parables flattened into moral slogans.” Sadly, I agree with her. If I’m going to find a home in the Catholic Church, it will be with thoughtfulness and care and a commitment to shape Catholicism for the better in whatever little ways I’m able.

In Catholicism the good, the true, and the beautiful are regarded as transcendentals, qualities that point beyond themselves and towards eternity. If there’s one thing I know about myself, it’s that finding the good in suffering, the truth in fantasy, and the beauty in the grotesque is my whole artistic calling.

So yes, maybe part of me is just intoxicated by stained glass and embroidered vestments and the way Latin feels in my mouth, by the beauty of the whole spectacle. But maybe beauty can be a starting point. Maybe, in some ways, beauty can be the whole point.

To live is to bear witness to a hundred tiny deaths of the self. If my best self is being reborn out of the ashes of my twenties as a queer Catholic woman, I’m ready to embrace her. I’m ready to cultivate those transcendentals wherever I can, and I’m ready to get over myself about it.

It’s no surprise the Met Museum’s Heavenly Bodies exhibit is the most visited Met exhibit of all time. God knows we’re all hungry for something transcendental in these dire, dreary days.

If you’ve read this far, thank you for being here! I publish essays about art and culture, spirituality and desire, and the life of the artist twice a month. Sometimes I talk about my experience in traditional publishing, or living as a working writer in New York City.

If you’re interested in learning more about mystic Catholicism, I recommend The Practice of the Presence of God by Brother Lawrence, The Way of the Rose: The Radical Path Of The Divine Feminine Hidden in the Rosary by Clark Strand and Perdita Finn, and the Jesuit Guide to (Almost) Everything by James Martin, SJ. I’m a loyal St. Anthony’s Tongue listener (be sure to follow

on Substack), and I never miss a essay. Her work on mental health, love and longing, academia, and the Catholic faith touches me deeply.That’s all I have for you this week, beloved. Be safe and well until we two meet again.

-S

Directly translated as “empty seat”: the period of time between the death of one pope and the appointment of another in which the papal seat is vacant.

They think there’s been no true and “valid” pope since the 1958 death of Pope Pius XII. Effectively, sedevacantists disagree with many changes ushered in after Vatican II in the sixties that attempted to reform church doctrine and liturgy for the modern era. They express this disagreement by saying, basically, “not my pope”. Amazing how a belief so self-serious can be terribly unserious.

Theologically, this movement puts ultimate importance on a “personal relationship” with Jesus Christ, working to convert all the nations of the world, salvation through faith alone, and centering written scripture as the literal, unchanging, infallible word of God. Culturally, it’s giving Hillsong United, WWJD bracelets, purity rings, meet me at the flag, Left Behind, Toby Mac…IYKYK

Obviously, I am not. But for the sake of the internet, and with my hand on the Bible: I am not.

This is of course a reference to Dasha Nekrasova, Catholic convert, co-host of The Red Scare Podcast and one of the archetypes the modern day ironic-until-its-not neo-conservative(?) it girl. I’ve listened to a Red Scare ep here and there, and I personally think we should let women in the public eye be meaner and intellectually incendiary and difficult to ideologically categorize. However, I do have notes about the flippancy with which Nekrasova seems to try on and then discard extremist-adjacent talking points, all with an unwavering affect that dares you to be offended by her.

I know this because it’s what my master’s thesis was about. Plenty of raised-evangelicals left their tradition of origin for agnosticism (according to the Pew Research Center 29% of U.S. adults currently identify as religiously unaffiliated) but the grip of liturgy on the American religious imagination continues to grow as well.

Acts 10:15

Christian empire has shaped Western capitalist cultural hegemony, it’s true. But I’d argue that this hegemony is an ultimate betrayal of the religion’s roots as an anti-imperial mystery cult rooted in radical equality and mutual service.

You did a beautiful job with this essay. I am not as familiar with Catholicism (I'm a woman who falls somewhere under the Pagan umbrella that can't quite find a label nor wants one), but the way in which you spoke about it, with such reverence, was stunning. I am looking forward to educating myself more on mystic Catholicism. Thank you, Saint, for a lovely and thought-provoking read.

So much of this resonates with me as a leftist Catholic who loves iconography and an occasional Latin Mass. Identity is complicated. So eloquent and well said!